2020 – ongoing

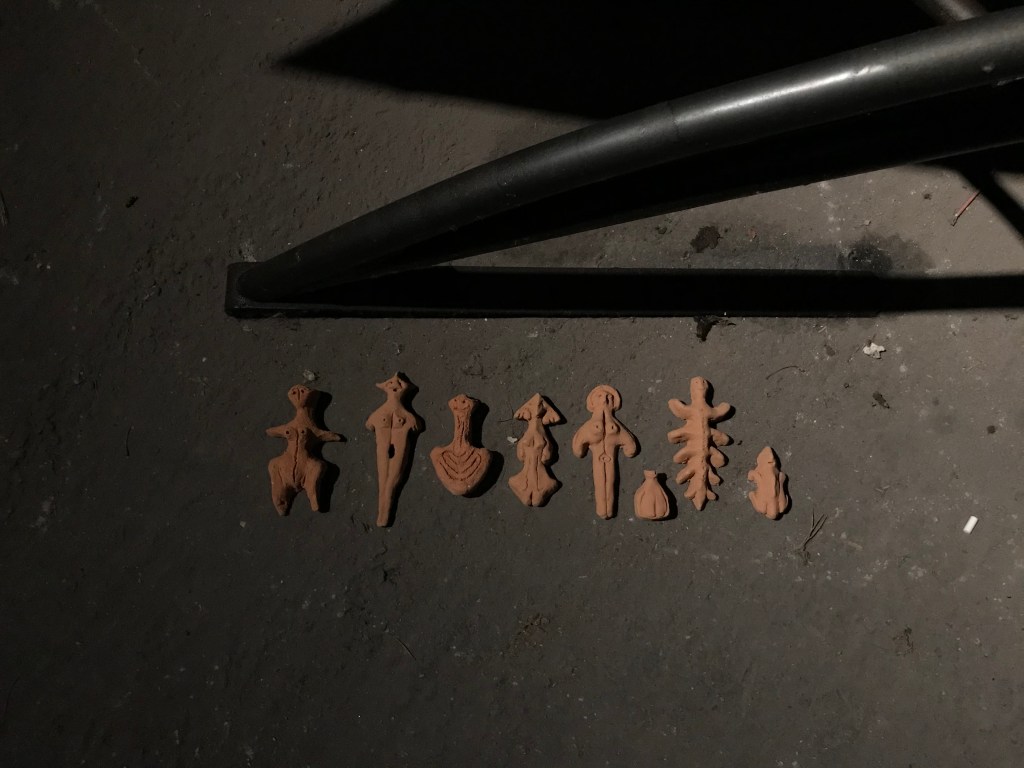

Golems are a self producing community, forming narratives about the surface, the ground, and the underground. The first figurines, shaped with clay in small sizes, were created by Ceren Oykut in 2020. Oykut discovered clay left over from road construction that was placed under cobblestones in a village in Germany. She quickly shaped it and gave it to the ceramic kiln. Each figure is activated by interacting with another. Each group baked together acquires a unique content. Golems multiply over time and expand the narrative.

Golems on cement, 2020

Golems on snow, 2021

[…] Oykut’s “Golems” (2020; Figure 8 here) are made from German material that she found. Oykut explains that she “discovered clay left over from road construction that was placed under the cobblestones in a German village”. In this way she literally incorporated Germany into her work.

With the figurines she seems to be saying: look, I am legitimated to use the sources that my new environment provides me with. It indeed seemed to be the artist’s aim to claim this position of being legitimated; she says: “I kind of want to be part of this international […] cosmopolitan environment,” but she stresses “without ignoring my own roots.” Truly, she keeps a non-belonging in her working life by appropriating new materials. The art critic Kosova stresses in an interview with Oykut that her combination of “real people” and “phantasmagoric monster-creatures” (Kosova Citation2018) signify conflicting notions and emotions. I suggest that the clay figures can be interpreted in a similar way but, in contrast to the installation I discussed above, they demonstrate more self-confidence in dealing with inner conflict and non-belonging. The form language seems to be better matched to the material. Looking at Oykut’s figures in terms of content, another development becomes visible. The figurines represent Neolithic females and in this way the artist formulates a “past perfect” with an ancient past and her personal experiences of moving. The Golems are portable reminders of earlier Indo-European migrant groups moving to the West, emphasizing women’s role in this context (Dexter Citation2011). Metaphorically speaking, the clay from Germany and the forms from Neolithic Anatolia (ibid., 35) combine both cultures but also bring together two temporal levels. It is a “visual past perfect.”

The analysis shows that Oykut reflects on her living in-between cities and art scenes on a temporal and material level. The most important aspect in this context is that the physicality of clay or plaster helps her literally in getting a grip on the city and dealing with emotional slippages that can potentially cause distress. As was emphasized by Lähdesmäki et al., materiality is strongly connected to bodily experiences of belonging or non-belonging (2016, 236). My analysis indeed shows that materiality in art can transform such bodily experiences into expressive aesthetics. Oykut’s heavy metal installation thematizes her struggle in not being able to speak German while her small but robust clay sculptures foreground her female experiences of non-belonging, through the reference to the female Neolithic symbolism. The artist uses a new technique to approach both topics and, most importantly, uses her non-belonging as a resource to develop a “visual past perfect” and she thereby overcomes linguistic boundaries while emphasizing her role as a female artist. […] *

*Quoted from the article How Turkish Artists Negotiate Non-Belonging Through a Visual Past Perfect – A Timely Artwork Analysis written by Verena Niepel (Taylor&Francis, 2025). Click to read the full article online:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08949468.2024.2409597#d1e455